Walter Womacka and East Berlin’s Socialist Face

One could argue that no one defined the face of “Berlin – Capital of the German Democratic Republic” more than visual artist Walter Womacka (1925 – 2010). A favourite of GDR leader Walter Ulbricht during the mid- to late-1960s during which East Berlin received much of its socialist makeover, Womacka was a key protagonist in the GDR’s “Kunst am Bau” (literally “art on building”) movement. This sought to ideologically mark East German cityscapes through large-scale, agit-prop artworks and Womacka’s creations graced a number of prominent buildings in the East German capital.

Eastern side of Walter Womacka’s 1964 mosaic “Our Life” on Berlin’s House of Teachers building (photo: M. Bomke).

Interestingly, more 28 years after the fall of the Wall, many of Womacka’s works remain intact and have even found a place in the iconography of present day Berlin. Given the ideologically charged debates around the legacy of much GDR-commissioned public art in the years following German unification in 1990, this was by no means a certainty. I think the reason for this lies in the way Womacka combined the aesthetic language of socialist realism with elements of folk art, an approach which allows many viewers to overlook the overtly propagandistic of much of his public art.

Womacka’s Alexanderplatz

Womacka’s best known work at present is likely “Our Life”, a monumental ceramic mosaic measuring 7 x 125 m which is installed on the “House of Teachers” on the south-east corner of Alexanderplatz, eastern Berlin’s central square. Installed in 1964, the piece has been described as “socialist realism par excellence: art in the public sphere as propaganda for collective harmony.” (Obituary for Walter Womacka in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Sept. 19, 2010), however, the work was well received and East Berliners gave it the nickname “the cummerbund”, a moniker which neatly sidestepped the work’s overtly ideological content.

In the call for proposals initially issued by the GDR’s Ministry of People’s Education, artists were advised that the winning design would necessarily demonstrate both an “educational” and “political” effect. Womacka’s design ticks these boxes nicely. Indeed, “Our Life” presents East German society just as the ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) wished it be: a monolithic entity in which citizens are united in their efforts to build socialism, their labour taking place under the Red Flag (not, it is worth noting, the GDR flag which appears nowhere in this design). It’s worth giving this massive work a closer look.

For the mosaic’s most prominent, west-facing side overlooking Alexanderplatz (top), Womacka chose to unite imagery of science and nature while suggesting how, through education, humanity can use the former to control the latter. This emphasis on science was, of course, a key tenet of the socialist / communist project. For the southern face of the mosaic (middle section above), the artist juxtaposes a scene of heavy industry and an artist’s atelier with the worker and artist looking across at each other, thereby suggesting mutual respect and an intrinsic connection as each works to construct socialism in their own way. For the north facing section (bottom left), Womacka returned to images of man’s mastery of science (and Womacka’s scientists are exclusively men) but then added that much loved motif of socialist iconography: space exploration.

For eastern side of the work, facing into East Berlin’s grand boulevard, the Karl-Marx-Allee, the emphasis is on leisure with scenes of dancing, a picnicking couple and bicycle racers flanking a trio of “socialist personalities”, a young woman dressed as a farm worker perhaps, a grim faced soldier bearing arms and a young worker flying a massive red flag. Apparently, initial drafts of this section had the soldier, without his helmet or weapon, being embraced by the young woman, an approach ultimately rejected for being incompatible with the dress code of the National People’s Army. (It’s interesting to compare this piece to “Our New Life”, a smaller scale mosaic he completed in 1958 for the House of Organizations in Eisenhüttenstadt, the GDR’s first planned city. While the two are distinct, the are a number of key parallels between the works.)

Bronze relief created under Womacka’s supervision for East Berlin’s House of Travel on Alexanderplatz (photo: author).

“Our Life” is not the only place where Womacka’s fingerprints can be found at Alexanderplatz. In 1969, as part of a project to beautify the square in honour of the GDR’s 20th anniversary, he oversaw a student collective which produced a massive 24 X 5 m bronze relief for the front of what was then the “House of Travel”, a modernist tower kitty corner from the “House of Teachers” and home to both the GDR state travel agency and its airline, Interflug. “Man Masters Time and Space” also recalls a number of leitmotifs from socialist iconography including the cosmonaut and pair of dynamic young people at its centre along with doves of peace at its right end.

Womacka’s “Fountain of People’s Friendship” on the Alexanderplatz in central eastern Berlin (photo: Manfred Brückels via WikiCommons)

For the square of Alexanderplatz itself, Womacka designed “The Fountain of People’s Friendship”. The fountain is 23 m in diameter with the fountains rising to over 6 m in height and quickly became a popular meeting place for young East Berliners, and a space carefully monitored by the People’s Police.

All three of these works by Walter Womacka can still be found, at their original locations, on or adjacent to the Alexanderplatz today.

“State Artist” By Conviction

While condemned by many as a “State Artist”, Womacka wore this label proudly and, like many of his generation, identified closely with the “Workers and Peasants’ State”. Womacka’s war time experiences, including service in the German Wehrmacht in the last stages of World War II, left him a convinced anti-fascist and so the GDR’s promise to create a new, just Germany resonated deeply with him. He received much of his formal artistic training in the GDR after his family relocated to the Soviet zone of occupation following the expulsion of ethnic Germans from the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia after World War II. From 1949 to 1953, Womacka studied painting at the Colleges of Fine Art in Weimar and Dresden and at the latter institution, he was mentored by its rector, a loyal SED member Fritz Dähn.

Walter Womacka, at left, in his atelier with two of his students in 1969 (photo: NBI (35/69).

Upon the completion of his studies, Womacka relocated to East Berlin to take a teaching position in the painting department of the College of Art in Weissensee. It was during this time that he began making a name for himself in circles of influence. In 1963, he was named department chair and in 1968 he succeeded his mentor Dähn as Weissensee’s rector, a position he would hold through to his retirement in 1988. As would be expected of a person in such a high profile position, Womacka defended the Party line publicly and he is on the record supporting the building of the Berlin Wall and the 1968 intervention of the Warsaw Pact to put down the Prague Spring. Furthermore, during his tenure as rector, more than 40 students were expelled from Weissensee on political grounds (Hannelore Offner, Klaus Schroeder: Eingegrenzt – Ausgegrenzt. Akademie-Verlag, 2000, pg. 640).

“From the History of the German Workers’ Movement”: Getting the Lead Out

Womacka’s political orthodoxy was testified to explicitly in his second major Berlin work, a coloured glass window which he designed for the GDR’s State Council Building in 1963/64. Entitled “From the History of German Workers’ Movement”, this monumental piece is two-stories tall and covers much of the back wall of the building’s entrance hall. The bottom third of the piece tells the history of German workers beginning with images of protests during the aftermath of World War I and in the Weimar-era before continuing upwards with scenes depicting the defeat of fascism and “new beginning”. The middle third shows joys and tribulations of “socialist construction” with the top section dedicated to “the socialist family – whose happiness – reliably defended by the armed forces – is based upon peaceful labour.” (Womacka quoted in Neues Deutschland, October 24, 1964).

“From the History of the German Worker’s Movement” by Walter Womacka in the former GDR State Council Building (photo: by Myriam Thyes via Wikimedia Commons).

Not surprisingly given its location and content, Womacka was keen that his piece not evoke a stained glass church window. To achieve this, he turned away from the leaded glass often used for stained glass windows choosing instead to employ a new technique which allowed him to use regular window glass. For this approach, Womacka first reproduced his designs by drawing them onto large sheets of glass (up to 5 m square) after which individual coloured pieces corresponding to his plan were carefully melted onto the glass surface. The effect of this technique is striking as, thanks to the use of regular glass, Womacka’s windows loses little of their transparency and the foyer of building enjoys considerable daylight. (This work can still be viewed in the former State Council Building which is now home to the European School of Management and Technology. This institution advertises itself as “The business school founded by business'”. From one establishment to the next, I suppose.)

For a sense of the difference this change in materials made, see below two of Womacka’s earlier window projects which utilized leaded glass. At left below, “International Resistance Fighters Against Fascism” from 1961 and to its right, a series of windows entitled “The Sciences” installed at the Humboldt University in East Berlin in 1962. Both of these works can still be viewed at their original sites.

“When Communists dream . . .”: Palace of the Republic

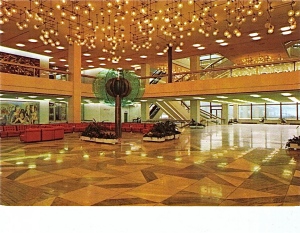

Berlin – Palace foyer with its distinctive “Glass Flower” sculpture (1977)

The Palace of Republic was the preeminent prestige project of the GDR and housed both the East German parliament and a number of cultural / recreational institutions. The building’s impressive foyer (see left) opened over two floors and featured 16 large format paintings commissioned from many leading East German artists, including Walter Womacka. Artists were asked to produce works reflecting on the theme “When Communists dream . . .” and while many of Womacka’s colleagues chose to interpret this theme rather broadly, he produced a painting which would’ve no doubt pleased the ideological hardliners who held sway in the upper echelons of the SED.

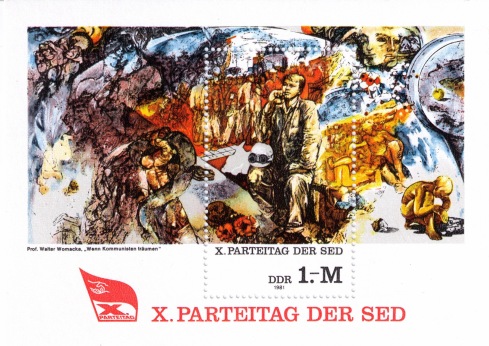

“When Communists Dream” by Walter Womacka in a GDR postal service stamp marking the SED’s 10th Party Congress in 1981 (photo: author).

In an expensively produced hardcover book published to mark the Palace’s opening in 1976, Womacka’s work is described as “a visual representation . . . of the historical mission of the working class . . . The artist demonstrates [in this painting] how the working class has been integral to all of humanity’s great achievements . . . At the centre of the work is a young worker. His clever, sensitive and inquisitive facial expression along with his powerful body symbolize the strength of the working class and how it takes on its historical mission with a sense of responsibility.” (Heinz Graffunder and Martin Beerbaum, Der Palast der Republik, VEB E.A. Seemann Verlag Leipzig, 1977, pgs. 43 – 50).

After the closing of the Palace in 1990 due to asbestos contamination, the 16 commissioned works from the Palace Gallery languished in storage, save for one exhibition in the German Historical Museum in 1995. This past fall, however, these works were included in “Behind the Mask”, one of the most important displays of GDR art since the fall of the Wall which was mounted at Potsdam’s Museum Barberini. I had a chance to see this impressive show and came away heartened by both the sensitive way in which the art was presented and its generally positive reception in the press. Perhaps we have finally entered a period in which GDR art can be considered free from the blinkered perspective of Cold War attitudes.

Socialist City Building in Marzahn

Womacka did not only leave his mark in central East Berlin, indeed his work can also be found on the city’s eastern edge in the district of Marzahn. This large scale housing estate for 170,000 residents was constructed over approximately 15 years beginning in the mid-1970s. A pedestrian street, the Marzahner Promenade, aimed to provide a commercial and social core for the district and Womacka provided a the design for a mural on a restaurant (house #40) as part of the public art meant to brighten the scene. This mural, entitled “Labour for the Happiness of People”, remains in place and above find some photos of the work by Richard Harrison.

Legacy

“Man, The Measure of All Things” in its new location on Berlin’s Friedrichsgracht (photo: author).

Predictably, Womacka was the focus of some criticism in the post-Wende period. Two major works, murals created for the East German Foreign Ministry, were lost to the wrecking ball in 1995/96 when the building they were in was demolished as part of a project to restore the historical footprint of that section of central Berlin.

Another was threatened in 2010, when the German Federal Government announced plans to demolish what had been the GDR’s Ministry for Construction on Berlin’s Breite Strasse. For the facade of this 70s-era GDR standard prefab office block, Womacka created a six-story tall mosaic of enamel covered copper tiles entitled “Man, the Measure of All Things”.

Bruno Flierl, a prominent East German architect and vocal advocate for the maintenance of GDR architecture and art in the public realm, suggests that Womacka’s choice of motif and title should be understood as “a visual appeal to the Construction Ministry to build on a human scale . . . The construction of buildings, indeed societies, needed to be done on a human scale. This was the artist’s opinion and it is reflected in this work.” If it was, I wonder whether Womacka’s work in the vast, faceless expanses of Marzahn showed him that his cri de coeur had gone unheeded.

“Man, the Measure of All Things” did not, however, fall to the wrecking ball, thanks to the “Friends of Walter Womacka”, a private group dedicated to keeping the artist’s work in the public eye founded by former members of the SED Central Committee’s Cultural Affairs Office. The Friends managed to convince WBM GmbH, one of Berlin’s public housing corporations, to dismantle the piece and reinstall it on one of its apartment blocks in the same neighbourhood as the former- Ministry building. While this was happening in the fall of 2010, however, Womacka fell ill and died before he was able to see his work in its new location on the gable of a block on the Friedrichsgracht near the Jungfernbrücke.

“On The Beach”: Womacka’s Greatest Hit

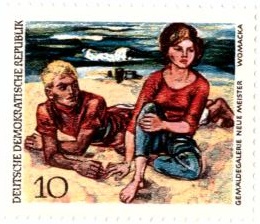

Walter Womacka’s “Am Strand” (“On The Beach”), here reproduced on a stamp from 1968 as part of GDR Post’s series on Dresden’s Gallery of New Masters (photo: author)

While Womacka is best known for the large scale public artworks he created as one of the GDR’s leading “state artists”, he was, both before an after German unification, a prolific artist whose work did not always display an agitprop hue. Womacka spent a good part of the year at a second residence on the Baltic coast, often working on landscapes and still life pieces. One work completed there in 1962, “Am Strand” (“On The Beach”) would become his best known painting. Visitors voted it “best work” of the 5th German Art Exhibition in Dresden in 1962/63 and, in following years more than 3 million copies of it were sold, primarily in the GDR, but internationally as well. Not only did the work have mass appeal, but the SED’s Central Committee even presented it to GDR leader Walter Ulbricht on the occasion of his 70th birthday in 1963.

What was it about “On the Beach” that resonated so deeply with the public and the Party? German writer and cultural critic Gunnar Decker, himself of GDR heritage, suggests that work offers considerable insight into the GDR desired by both its leaders and many of its citizens:

“A young couple just as Ulbricht and Honecker imagined was right for the GDR: without any distinguishing characteristics, friendly, healthy, relaxing on the beach as if just having come from a Subbotnik (ed. Soviet term for volunteer work contributing to the common good and a feature of GDR everyday life, particularly in the 50s and 60s), gathering energy before rededicating themselves to the construction of socialism. Decisive for the popularity of the painting with the public (it would become the consensus artwork for East German living rooms) was something else: its expression of modest good fortune, happiness, even coziness (ed. original German is Gemütlichkeit).” (Gunnar Decker, 1965, Carl Hansen Verlag: München, 2015 in Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung licensed edition, pg. 196.)

After the Wende, “On The Beach” went into storage at Dresden’s Gallery of New Masters only to reappear in 2004 as part of a Womacka retrospective in the museum in the socialist planned city of Eisenhüttenstadt. There the painting remains, once again in storage, but a second, apparently identical copy, created by the artist at the same time as the first, has been on display at various locations since his death in 2010.

Lithographic reproduction of Womacka painting of “Berlin – Capital of the German Democratic Republic” (1982) which hangs in our living room (photo: author).

I love your article! I think it’s a good thing that so much relicts of Walter Womacka have been saved. It’s a kind of ‘GDR-sauce’ in the modern world. It just belongs to former East Berlin! Did you also visited his grave on Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde?

Thanks for the kind words, Wilfred! No, afraid I didn’t make it out to Friedrichsfelde on this visit. Next time perhaps. It’s been a while since the last time I was there.

Nice to see that not all has been erased.

While much of the GDR-era has been removed from eastern German cityscapes, there is still a remarkable amount to find. Often, however, one has to know what one is looking for. While it is fair to label Womacka an “artist of the state”, he left his mark on 20th c. Berlin and it’s good to the city being willing to weave this history into the fabric of the present day.

Pingback: A Visit to Staatsratsgebäude in Berlin via @fotostrasse