Historical Memory and Berlin’s East Side Gallery

Over the past couple of weeks, the fate of the longest remaining original section of the Berlin Wall, the 1.3 kilometre East Side Gallery, has received considerable attention not only in Berlin but in the world media. The story of how a private developer seeking to erect a luxury condo where the Wall’s death strip once ran has enjoyed more than its requisite 15 minutes thanks to a media savvy protest campaign and the participation of former-Baywatch star David Hasselhoff.

The developer of the luxury condo, Living Bauhaus (honestly, you can’t make this stuff up) incurred the wrath of Berliners and their supporters by removing one section of the Gallery to allow for access to a pedestrian foot bridge which they are building across the River Spree as the first step in the project. Locals were outraged that the work had proceeded without any warning or, they felt, substantive consultations. After several large protests and a petition campaign (which continues on here), the project has been put on hold, but there is no guarantee that this stretch of the Wall will remain intact as things evolve.

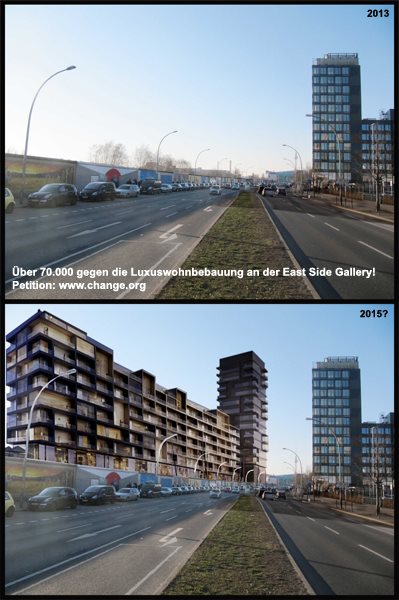

Top – East Side Gallery as it is today; Bottom – Living Bauhaus’ condo which the Mayor of Berlin’s Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg borough has suggested “leaves the East Side Gallery looking like a garden fence” (Tagesspiegel, March 2013)

A History of the East Side Gallery

The 1.3 kilometre stretch of the Berlin Wall which has come to be known as the East Side Gallery is a collection of more than 100 paintings done by international artists during 1990 as the process of German unification unfolded. The Wall on which these works were done was the interior barrier that East Germans would have seen as a white-washed cement surface. Between this structure and the River Spree was “the death strip”, entry into which invited live fire from the many border guards who patrolled this sensitive border between East and West Berlin.

In the aftermath of the Wall’s breach in November 1989, Berliners were understandably keen to remove this barrier and symbol of oppression as quickly as possible. If I were writing for British newspaper, I would now have to insert a reference to “typical German efficiency” here, but in this case it would be justified for Berliners took this task with such gusto that within a few years, it was genuinely difficult to still find traces of the Wall in the Berlin city scape. That the Gallery has survived this long is largely due to the engagement of the artists’ and their supporters and it has been heartening to see in the reports from the demonstrations that Berlin’s twenty-something activists are on board with saving this important site from the wrecking ball.

- The GDR’s last leader Erich Honecker as the “Sun King” (1999, author’s photo)

- Mural on the East Side Gallery (1999, author’s photo)

A Few Caveats

That said, I have some reservations about the Gallery and its usefulness as a site for conveying the realities of divided Berlin. It’s true that the Gallery is the largest remaining stretch of Wall in its original location and these important characteristics are the reason I support its continued existence. However, I fear that the site has the potential to mislead and misinform visitors. As pointed out above, through the presence of the paintings, visitors are presented with something that does not actually represent the Wall’s appearance during the 28 years it was in use. This is exacerbated by the fact that there’s little in the way of interpretative plaques and the like to provide any information about the Wall, the GDR’s border regime or this specific location, so visitors are left on their own to navigate the meaning of what they are seeing. Finally, there’s nothing particularly interesting about this stretch, at least in an historical sense. Not every section of the Wall was equally eloquent in telling the truth about the its purpose and the oppressive regime its served and I would suggest that, had consideration been given to which section of the Wall ought to be preserved for the purposes of telling the story of Berlin’s division back when such decisions could have been made, this 1.3 km stretch would not have made anyone’s list.

As is always the case when it comes to issues of historical memory, the East Side Gallery represents a compromise resulting from the interplay of competing narratives of a past and the concrete possibilities still extant to present this history. I’m not saying the result is terrible, but it is a compromise and should be understood as such.

Berlin – “The Rome of the 20th Century” – Gets It Right, Sort Of

When I first got wind of this matter from a friend in Berlin (thanks SIbylle!), I was surprised that the city would have put its foot in it like this. If there’s a place in the world where there’s a well-developed sense of historical memory amongst the city’s elites, I would have thought it was Berlin. Then I got thinking about it and realized that one reason why the city authorities might have dropped the ball here was the belief that they had already got it right with this part of the city’s history when they opened the Berlin Wall Memorial, an open air museum/memorial on the site of the Wall as it ran between Berlin districts of Middle (East) and Wedding (West).

If there is a place that evokes the painful reality of separation for many Berliners and Germans, it is the Bernauer Strasse. This is due to the fact that the Wall ran through two densely populated residential districts at this point and, in its early years at least, saw a number of dramatic escape attempts, many of which were captured on film and continue to be shown on anniversaries and the like. The 1.4 kilometre site now contains both Visitor and Documentation Centres, a chapel (built on the site of the Church of Reconciliation (you really can’t make this stuff up), a place of worship stranded in the middle of the death strip for years and which GDR authorities had blown up in 1985) and a Memorial that is intended to convey the reality of the Wall as it existed at the time of its breach and which contains its last remaining section in the street.

An attentive reader will note my careful choice of wording above: “intended to convey the reality of the Wall”. Yes, as you may have surmised, the Berlin Wall Memorial is not a carefully preserved section of the border fortifications but rather a “historical recreation” what once stood on the Bernauer Strasse. The site’s overseers have done an excellent job in conjuring the Wall and its systems in the Memorial and the interpretative content available all over the site is exemplary. There is a moving tribute to the victims of the Wall, including pictures and biographies, a number of large scale murals on surrounding buildings feature images taken from photos at those sites so that people can get a sense of the area as it was. But the fact remains, in their haste to rid themselves of all vestiges of the Wall (understandably perhaps but nonetheless . . .), Berliners managed to deny future generations of a site which kept the border fortifications intact to the extent that one could easily understand the reality which the Wall imposed on everyday lives.

- The west side of the remaining original piece of Wall at Bernauer Strasse (note where it has been chipped away by souvenir seekers) (2011, author’s photo)

- No Man’s Land at Berlin Wall Memorial at Bernauer Strasse (2011, author’s photo)

- Rusted bars as part of the installation marking site of Berlin Wall at Ackerstrasse/ Bernauer Strasse (2011, author’s photo)

- Mural with image of Wall as it was at Gartenstrasse/ Bernauerstrasse in 1989 (2011, author’s photo)

- Memorial to victims of the Wall at Berlin at Bernauer Strasse (2011, author’s photo)

- Photo of Chris Gueffroy (bottom row right) in Bernauer Street memorial to Wall and its victims (photo: author).

The Provisional Berlin Under Siege

Berlin has enjoyed incredible cachet amongst youth from the around the world, artists and activists and culture mavens since the fall of the Wall. I’d argue that a lot of this has had to do with the excitement that this city in transition, a place characterized by the unusual and transitional, offered those who settled there. Berlin was, as its Mayor Klaus Wowereit put it a few years back, “poor but sexy” and that made for a great place to be young and adventurous. As the 25th anniversary of unification approaches next year, there’s no question that Berlin is slowly becoming a “normal” city and an unsurprising corollary of this is that much of what has made it unique and attractive is coming under increasing pressure. The development of the East Side Gallery site is one example of these pressures and I would imagine that frictions around the erasing of the more prominent examples of Berlin’s “other” status will likely be at the centre of that city’s politics in the coming years.

I’ve always loved these unusual Berlin scenes and am loathe to see them disappear, but there remains plenty of room for “Off Kultur” in the city, it’s just no longer going to be concentrated in Middle or P’Berg. “Go East Young Man/Woman!”

Change is inevitable, especially in cities, European cities where people have been building for the ages for the ages. As my friend Martin, a Wessi who relocated to P’Berg over twenty years ago, offered on the East Side demonstrations, “I’m ambivalent to the demos; it was no secret what was going to happen there . . .” That’s not simply resignation there, but rather an acknowledgement that time does indeed go on and that things do change whether we like it or not (and I don’t!).

****

And as a special treat for those of you who have persisted to the end, below find David Hasselhoff performing his German #1 hit “Looking for Freedom” on the Berlin Wall in 1989 (you simply can not make this stuff up).

Thank you for this well-researched and well-written blog on past and continous stories about the GDR. My first thought on this mercenary project was: “How can politicians be so ignorant of the history that they allow a building company to erect luxury apartments on a site where people were killed. Who could actually image to live on the former death strip behind the painted concrete wall where tourists stroll along and smile in their cameras to document that they were there?

Well, the irony is that those luxury condos might be erected on a site that surely once was part of the “antifascist protection wall”, i.e. death strip, but that after the fall of the wall elsewhere also – quite uncontroversially – has been used by club owners and other fancy cultural entrepreneurs. It is exactly this clientel the investors are aiming at — and they love it, first partying then residing on poisened ground.

On the other hand. Don’t we all live on former death strips?