The Darth Vaders of East German Soccer: BFC Dynamo

Most sports leagues have a team that functions as a villain, a target for the antipathies of practically everyone who isn’t one of their fans. In baseball, the New York Yankees have worn the black hats, both literally and figuratively, since the 1970s when George Steinbrenner took over the team. In NFL football, the New England Patriots have attracted considerable scorn thanks to the their coach Bill Belichick, a man with the few scruples and even fewer social graces. In the hockey world, the 70s-era Philadelphia Flyers (aka “The Broad Street Bullies”) invited the disdain of practically every fan outside of the “City of Brotherly Love” for their successful redefinition of the sport to include a healthy dollop of Kubrickian ultraviolence.

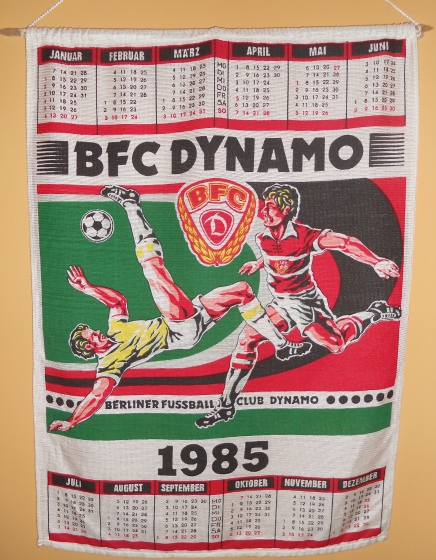

A BFC wall calendar from 1985 purchased on my visit to East Berlin that spring. I think I got this at a kiosk in the Friedrichstrasse station. It measures 56 X 41 cm. (photo: author).

Lists of sporting villains are constantly being revised (mainly in bars and on sports talk radio), but I would contend that all would be enriched through the inclusion of East Germany’s most reviled soccer team: Berlin Football Club Dynamo (BFC Dynamo). Dynamo dominated the East German first division, the Oberliga, in the 1980s winning the league championship ten years on the trot from 1978-79 through to 1987-88. While such a run of success would stoke resentment in any setting, the disdain of East German soccer fans towards Dynamo was based not only the team’s dominance but also on its close connection to the GDR’s hated secret police, the Stasi.

A Brief History

Mural at SC Dynamo’s Sportforum; it features uniform clad People’s Police officers coming to train after a day on the job (photo: author).

The roots of BFC Dynamo are to be found in the Berlin Sport Club Dynamo, an organization for employees of the MInistry for State Security and the People’s Police in the East German capital founded in 1953 and modelled after Dynamo Moscow Sport Club which had close ties to the KGB SC Dynamo offered training in a variety of sports including swimming, track and field, volleyball, gymnastics, etc.. and soon became the home club of many of the GDR’s top athletes with conditions among the very best on offer in the country. (Not surprisingly, SC Dynamo athletes were involved, often unknowingly, in the GDR’s clandestine doping program for the country’s elite athletes. Indeed, a number of the most notorious East German doping cases -including a number of highly successful, female swimmers – were members of the club.).

A second section of mural at Sportforum, its mingling of workers, police and athletes testifying to a GDR ideal (photo: author).

While the soccer section of SC Dynamo enjoyed some limited success in these early years, it was only once it was separated into its own Football Club that the team began to emerge as a force in East German soccer. The creation of the Berlin Football Club Dynamo took place as part of a nationwide effort to improve the quality of East German soccer that began in 1965. By creating ten Football Clubs, the intention was to offer a high level of training the most promising footballers so that they might realize their full potential. While the vast majority of the Clubs were independent institutions, two (BFC and FC Vorwärts Frankfurt) were formally associated with the Ministry for State Security and National People’s Army respectively and these connections to what were central institutions of the East German state benefitted both Clubs significantly. By the late 1970s, Dynamo was home to many of the GDR’s best players and had laid the groundwork for its remarkable run of success by establishing what many considered to be the country’s best youth teams.

Erich Mielke, Dynamo and the “Penalty of Shame”

Thanks to its close links to the Stasi, Dynamo counted Erich Mielke, the GDR’s Minister of State Security, as its biggest fan and “Honorary Chairman”. Mielke’s support was, by all accounts, considerable and included helping assure that the most promising young talents were “steered” BFC’s way. Many East German soccer fans, however, contend that that Mielke’s influence also extended to include sway over referees. Critics of BFC often point to the fact that East German officials wishing to officiate international competitions required visas that needed Stasi approval, contending that this fact alone would’ve made many referees susceptible to aiding BFC’s cause.

“Fair Play”: Rather ironic theme to BFC poster given the the Club’s reputation as “Schiebermeister”, (Champion Cheaters) (photo: author).

For many, the best evidence of the systematic preferential treatment enjoyed by BFC is found in what has become known as “The Penalty of Shame”, a controversial free kick awarded to Dynamo in March 1986 during a match between it and Lokomotiv Leipzig, BFC’s closest rival for that year’s title. Near the end of the closely fought match, the referee sent Lok’s captain from the field with a second yellow for leaving a wall before a free kick could be taken – a harsh decision by most footballing codes. Then with the final whistle looming and with Lok leading 1-0, a BFC striker fell to the ground in the Lok penalty area for no apparent reason and the referee didn’t hesitate to signal for a penalty kick. The Leipzig stadium was thrown into tumult and the radio commentator channeled the sentiments of thousands of GDR soccer fans: “THIS CAN NOT BE HAPPENING!” It was, however, definitely happening and, of course, BFC equalized. A few weeks later, Dynamo won the league over Lok by – you guessed it – two points, the difference being the draw in Leipzig.

At the post-match press conference, facing a room of livid Leipzigers, the East German Football Association’s number two promised action and, amazingly, delivered. The referee disappeared from the officials list, confirmation for most fans of their suspicions that games had indeed be justified. (According to a wonderful article by Christoph Dieckmann in Germany’s DIE ZEIT newspaper in 2000, however, the facts of the case appear to get in the way of this myth).

BFC Fans Flirt with NS-Chic

Until BFC established itself as the cream of East German football, its support was relatively modest and made up largely of employees of the GDR’s security services (People’s Police, Stasi, Corrections/Customs). With the successes of the late 70s, however, the team began to attract younger fans, primarily from the central districts of Prenzlauer Berg and Mitte to matches at the Jahn Sportpark directly adjacent to the Berlin Wall. Frank Willman’s book Stadionpartasanen (Berlin: Neues Leben, 2007) includes interviews with a number of active members of the BFC fan scene from the last decade of the GDR and these go a considerable way to given a picture of the situation.

Pennant from 1989-90, the last year of GDR Oberliga. Thanks to D. Klatte for this contribution (photo: author).

In Berlin, 1. FC Union were clearly the #1 in terms of fan support, regularly drawing crowds of close to 20,000 and sending 2- or 3,000 to the Club’s away games. The group of committed BFC fans numbered in the hundreds, but soon learned to compensate for their numerical inferiority through superior organization and acts of intimidation. Derby matches between the two clubs took place at the “neutral” location of the Stadium of World Youth and typically concluded with BFC fans chasing their rivals to the Friedrichstrasse train station down streets closed to traffic while police watched the chaos with practiced disinterest.

Confrontations between the two fan groups became commonplace in Berlin during the early to mid-1980s with Dynamos’ fans gaining the reputation of being particularly brutal in their violence, but each Club defended its turf from encroachment by opposing supporters. One particularly “hot” location was the central Alexanderplatz, a main meeting place and transit hub. BFC’s hard core made the Self-Service Restaurant located on the square its headquarters for a number of years and would “hunt” any opposing fans, Unioners and others, foolhardy enough to venture onto Alex unaccompanied. Willy, a member of this cohort describes the scene as follows:

“Our meeting place was the Self-Service Restaurant (Selbstbedienung in German, SB for short) . . . In 82, 83 I was there every day. I just decided not to go to work any more and the SB was where we gathered. Sometimes I was there from 8 in the morning. We

had our table right next to the door. From there you had a great view of what was going on. Right next to Alexanderplatz station and we knew the schedule, so we always knew right away when “fresh Saxons” had arrived.” (pg. 31, Stadionpartasanen)

In the mid-1980s, BFC’s hardcore fans adopted the skinhead fashions known from Western Europe and their shaved heads, bomber jackets and Doc Martens quickly helped them earn a reputation of being “neo-Nazis”. If participants of the time are to be believed, this choice of outfit and appearance should be seen as an act of rebellion largely free from political content:

“We called ourselves “right” (rechts in German, a term that denotes radical right-wing or Nazi ideological affiliation) at the time, but that was more of a provocation. None of us really knew anything about politics. But to raise your arm in the Hitler salute in from of the People’s Police was a real kick. You did that and for some them their whole world just fell apart.” (pg. 32, Stadionpartasanen).

Police, Stasi and the Party were duly alarmed at this development but at a loss as to how to respond or simply in a state of denial. Complicating the matter was the fact that many BFC fans involved with these provocations came from families linked to the state’s security apparatus. As one Stasi officer charged with overseeing the BFC fan base offered in a post-1989 interview, “Whenever something unpleasant happened, it was claimed that it couldn’t have been BFC fans. Things that “shouldn’t be” were ignored or relativized.” (pg. 145, Stadionpartasanen).

Playing the Role: BFC on the Road

There are numerous accounts of the hostility levelled at BFC in East German stadiums during their championship years. Dynamo’s players, however, appear to have taken it all in stride. Bernd Schulz, the BFC player who drew the “Penalty of Shame” with his plunge to the earth in the Leipzig match, recalls:

“The hate towards BFC got bigger every year. Of course, it did. In places like Aue, Böhlen and Zwickau, they might not have seen an orange in months and then we’d come in from Berlin, sit ourselves in our bus after beating their team and unpack our lunches with oranges and what not right in front of them. They’d go nuts!”

BFC fans practice some provocative loitering in the shadow of Dresden’s Lenin Monument (photo: unknown).

The team’s goalkeeper Bodo Rudwaleit offers, “We were a great team. We went out and wanted to show those assholes. And usually we did, and then it was ‘Con Men Dynamo!'” When asked about the perception that referees favoured BFC, he’s indignant at first but then reflective: “BFC referees! Although on some decisions, I do remember thinking, ‘My God! Is that really necessary?’ But really, it didn’t matter how the ref did, everything was blown out of proportion with us.” (“Der Schand-Elfmeter von Leipzig, Die ZEIT 33/2000).

“Death to the Traitor”: BFC’s Lutz Eigendorf

The long arm of the Stasi is also suspected to have played a role in the death of former-BFC player Lutz Eigendorf as the result of a car accident in Braunschweig, West Germany in March 1983. Eigendorf was one of the GDR’s most promising young players and important member of BFC when he defected to the Federal Republic following a friendly match between Dynamo and West Germany’s 1. FC Kaiserslautern in in Giessen in March 1979. Erich Mielke was livid with this news and placed Eigendorf under close Stasi surveillance. After Eigendorf’s accident, some pointed the finger at the Stasi, but police closed the case arguing that the player’s elevated blood alcohol level supported their view that his death was not suspicious. (Witnesses who were with Eigendorf before the accident, however, told police that while he had been drinking, he’d had very little and certainly not enough to create the blood alcohol levels found in his system.)

After unification, the opening of the Stasi files revealed the extent of Mielke’s operations against Eigendorf including details of possible ways of killing the player. In recent years, further circumstantial evidence implicating the Stasi in the death has surfaced. This includes documentation showing that the supervising officer on the case received a large cash award on the night of Eigendorf’s death and a statement from a former Stasi employee that he was approached to kill the player but did not. While definitive proof may never be found, it seems likely that Mielke’s organization took revenge on Eigendorf as they would have with one of their own “traitors” who had defected West.

Eigendorff’s death found an echo, amazingly, inside BFC’s home ground, Jahn Sportpark, during a match in April 1983 when a group of fans managed to unfurl a banner reading “Iron Foot [E’s nickname], we mourn you!”. The display of such sentiments in front of Mielke and his colleagues was a brazen act of provocation and, according to a Stasi officer charged with overseeing BFC’s fans, this incident marked a turning point in authorities’ assumptions about the team’s supporters. Where previously, the Stasi and People’s Police in Berlin had tended to turn a blind eye to the sins of BFC fans or blame followers of Union Berlin for street violence, the banner incident opened their eyes to the attitudes of at least some of “their” boys. (pg. 134, Frank Willman (Ed.), Stadionpartasanen. Berlin: Neues Leben, 2007).

Dynamo After Unification

Terrace and scoreboard at Sportforum stadium. I’ve only ever visited when no match is being played; it’s safest that way (photo: author).

In the aftermath of German unification, Dynamo Berlin couldn’t jettison their titular connections to the Stasi fast enough and renamed themselves “FC Berlin”. The name change, however, could not stop their descent into the lower reaches of German football and the club currently competes in a regional league for northeastern Germany that corresponds to 5th division level. BFC plays its home games at the Sport Forum in Berlin Hohenschönhausen, a dilapidated stadium on the former grounds of the Sport Club Dynamo. Today the Club is best known for the willingness of some of its fans to participate in the so-called “third half”, that is, physical violence in and around football matches (see video from BFC supporters attack on members of 1. FC Kaiserslautern during a first round match of the 2010 German FA Cup competition below. I believe the images speak for themselves.)

In 1999, the FC decided to return to their traditional name and rechristened themselves BFC Dynamo, however, they were unable to secure the rights to their original logo and have worked with alternatives since. In 2009, BFC introduced a new team logo which immediately caused significant controversy in that it spelled the word “football” with a double-S and in a Gothic German type that evoked for many the insignia of the Nazi’s SS. Some observers charged that this was an attempt to court fans in the neo-Nazi scene, a demographic with which some followers of the Club have been associated in the past. BFC officials initially rejected the criticism, but later modified the logo’s font.

Controversial first version of 2009 BFC logo. Note the double-S in the word “Fussball” at top centre – this is an unusual choice in written German as, typically, the Eszett ªß” is used.

Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark – May 2014

When the occasion warranted it, BFC Dynamo played its home matches at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn Sportpark in East Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district. The stadium was the largest in the East German capital, however, it was located directly on the Wall, a fact that caused GDR authorities more than a couple of sleepless nights. The fear was that football fans might use their numbers to storm the border and so matches carried out at the Jahn Sportpark were typically accompanied by large numbers of People’s Police and other security personnel (read: Stasi).

I was able to visit the stadium this past May and got the pictures found below then. While the stadium has seen some renovations in the past 25 years, the scene is not all that different from the one that would’ve greeted East German football fans attending a match in the mid- to late-1980s.

Last week, German newspaper DIE ZEIT had an interesting piece which delved into a claim that “Dynamo” is the most prevalent team name in world soccer. There’s a great story about a group of hobby players in West Germany in the 1980s who named their team Dynamo Windmill and were subsequently barred from participation in their local men’s league by the regional FA. It’s quite something so I have translated the piece and you’ll find it in the pdf below.

A Relic of Communist Sport – English

Great post John Paul,

I do not think there is any ambiguity about their attempt to attract fans from the extreme right. The runes were only one manifestation of the club recognizing their potential fan base and seeking to develop their support. The few times I have attended their matches, I was treated to continued neo-Nazi chants, salutes, and violence. Interestingly, the Hells Angels have developed quite a close connection to the club, perhaps for these reasons. In my memory, Hells Angels’ colours and Confederate flags abounded in and around the stadium.

The story of the appropriated championship stars is also pertinent to East-West relations in the refusal to recognize their DDR victories but also the refusal to see their championship stars as fairly won without political interference.

Great stuff, JP – I think I once found something in the DTSB archive about the strange case of Dynamo Windrad; will have to look it out for you!

In slight defence of the modern-day BFC: I’ve seen numerous games there in the past few years and there are plenty of regular fans around the club. They are by no means all neo-Nazis… hell, one of the banners regularly up at the Sportforum quotes The Smiths! (“There is a light that never goes out”)

There’s another banner with the flag of Norway (who beat Nazi Germany in an international in 1936 which allegedly was the only time Hitler attended a football match) saying: Berlin 1936, tak Norge (thanks, Norway).. The first anti-fascist football fan initiative in Berlin after 1990 (AFFI) was also started by BFC/Eisbären Berlin fans.

Thanks for this, Steve.

Pingback: Eigen-Sinn: The Battle for East German Football | The Socialist Party Portsmouth BranchThe Socialist Party Portsmouth Branch

Pingback: Whose Game Is It Anyway? | fifteeneightyfour

Pingback: Defectors use soccer to escape persecution in Eritrea | Fusion

Pingback: Guide to a City's Soccer Clubs - Berlin ⋆ Soccer Minnows

This is a great article. I am currently doing a university research project on the football fans of Berlin so this has really helped. I have some more questions though, would you be able to answer?

Pingback: The Team They Love to Hate. Life as a Dynamo Berlin Fan (16) - Radio GDR -East Germany Podcast

This is one of the best articles I have read on BFC Dynamo! I think there has been quite a bit of rather sloppy sensationalist writing over the years when it comes to BFC Dynamo. Simplifications (and sometimes more or less rumors) have been reproduced and presented as facts, seemingly without any real attempt to fact check, question, understand or put things in their proper context. That have made me a little bit sad. BFC Dynamo was not all stealing and cheating during the East German era. There were also a lot of skill and hard work behind the club’s success. Not least, the club had a bunch of great players. They deserve better. I read a few pages in the book “Football Against The Enemy” by Simon Kuper. Simon Kuper is a great author. His book is definitely not a piece of sloppy writing. But he writes that “Mielke loved his club and made all the best players in the GDR play for it (one was Thomas Doll, now with Gazza in Lazio.) He also talked to referees, and Dynamo won lots of matches with penalties in the 95th minute” I wonder if he checked the statistics before he wrote that? First. Who are all these players he talks about? Any names? Waldemar Ksienzyk, Thomas Doll and Frank Pastor were surely recruited from other teams in the 1980s (as well as a number of less important players). But all three came to BFC Dynamo after the team they had played for was relegated to the DDR-Liga. That is hardly spectacular. Rather normal I would say. But apart from them, most of the top-performers of BFC Dynamo in the 1980s came through the club’s own junior team as far as I can see? (It is important to say that BFC Dynamo was extremely privileged when it came to recruiting talent, but in that case, we mostly talk about young players who were then developed in the youth academy, not established players who went straight into the first team.) Second. BFC Dynamo ”won lots of matches with penalties in the 95th minute”. Really? The DDR-Oberliga was not played behind closed doors. There are tons of statistics available for all seasons. It is all out there for anyone to check. I checked all league matches that were either (a) won by BFC Dynamo with one or two goals or (b) drawn by BFC Dynamo, from the 1978-79 to the 1987-88 season (the ten league seasons won by the club) . My conclusion is that the famous extra time did not play a decisive role for BFC Dynamo. I found only two matches won by BFC Dynamo on extra time (HFC Chemie – BFC on 12 April 1984 and BFC – 1. FC Union Berlin 5 March 1988). And none of those matches were won by BFC Dynamo with a penalty (that is, with the winning goal scored on penalty). Then, I also found five matches equalized by BFC Dynamo on extra time. Three of those matches was equalized by BFC Dynamo with a penalty: FC Carl Zeiss Jena – BFC 29 November 1980, the match against HFC Chemie mentioned above (which is thus counted for twice, as BFC Dynamo scored a winning goal after the penalty) and, of course, the infamous match 1. FC Lokomotiv Leipzig – BFC 22 March 1986. (But the “Shame penalty” has been proven to be correct, according to Frank Willmann). So, here we have 7 matches won or equalized by BFC Dynamo on extra time (one match counted twice). Two of those matches was equalized by BFC Dynamo with a penalty. In ten seasons! We are talking about 260 league matches in total. I have certainly missed one or two, but If anyone find Simon Kuper’s “lots of matches won with penalties the 95th minute”, please tell me where they are. Thanks again for a great blog! Kindest regards. /Erik

Thank you Erik, For both the kind words about the blog and post, but even more for the excellent, well-researched comment.

I think you’re right about Dynamo’s reputation colouring views of the club. There were a lot of dynamics at play in regards to the movement players, the teams treatment by referees, etc. which mirror practises we see all the time at “big” clubs today. The affiliation with Erich Mielke and the Stasi has understandably tarnished the standing of those championship teams, but with the benefit of hindsight, it would be nice if the club’s sporting achievements received more respect.